press

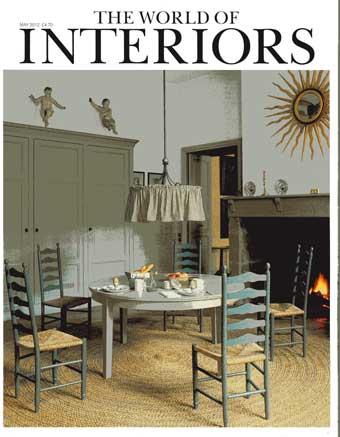

May

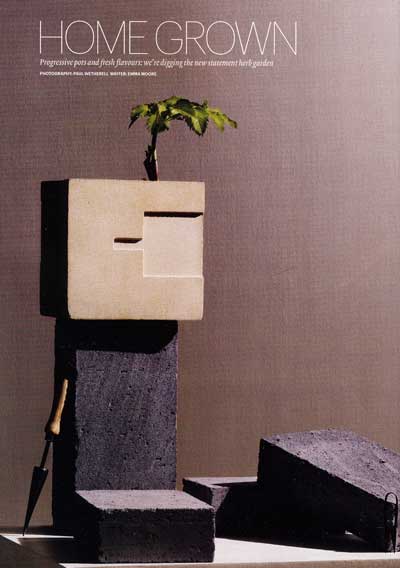

2012 Concrete

planters

December 2011 Concrete figurines

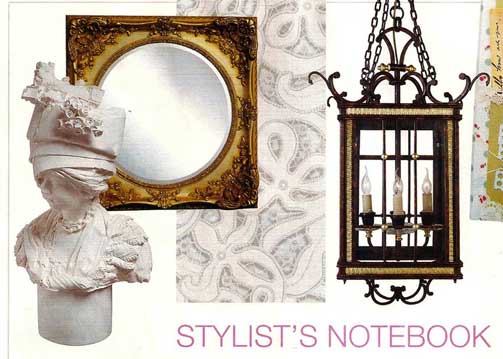

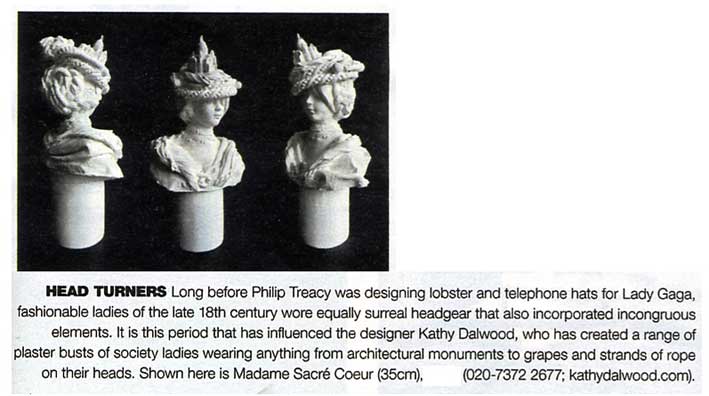

October 2011 Demoiselle D plaster busts

September 2011 Ms Chattanooga plaster busts

May 2011 concrete

figurines

April

2011 concrete

tassels

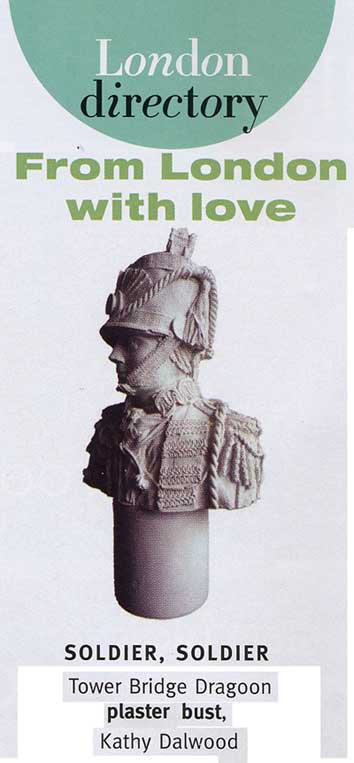

January 2011 Tower Bridge Dragoon

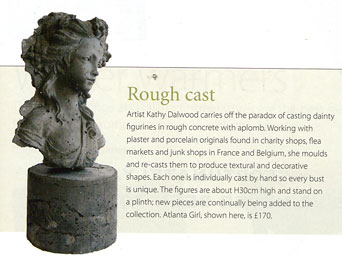

Concrete Figurine: Atlanta Girl

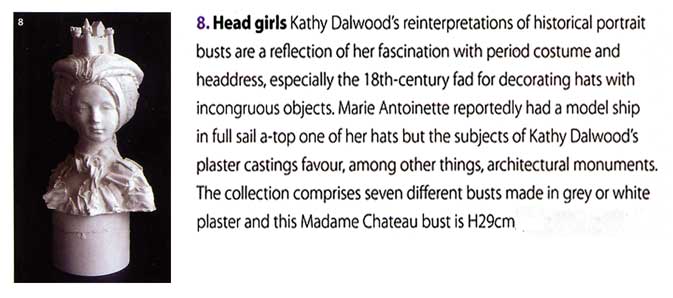

November 2010 Plaster Bust Collection

October 2010 Plaster Bust Collection

THE HUNTER & GATHERER

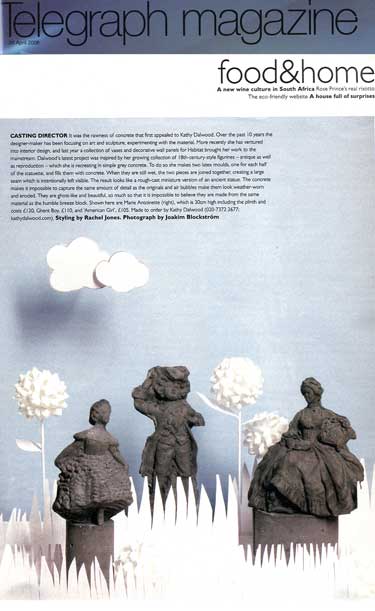

Post title: CASTING ABOUT

click image

click image

August 2010 Plaster Bust Collection

June 2010 Plaster Bust Collection

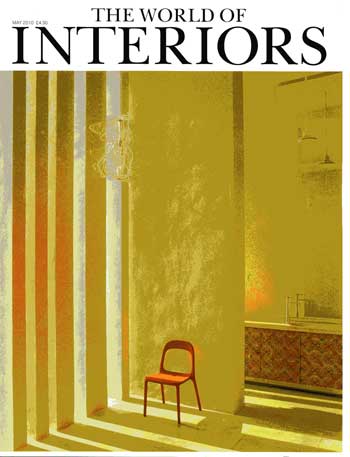

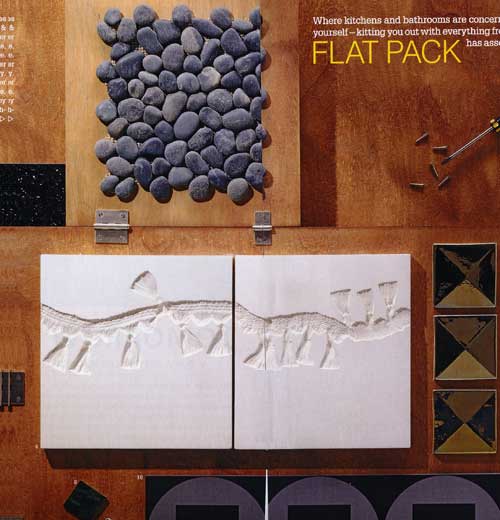

May 2010 featuring tiles & friezes

April 2010 featuring figurines

March

2010 featuring

figurines

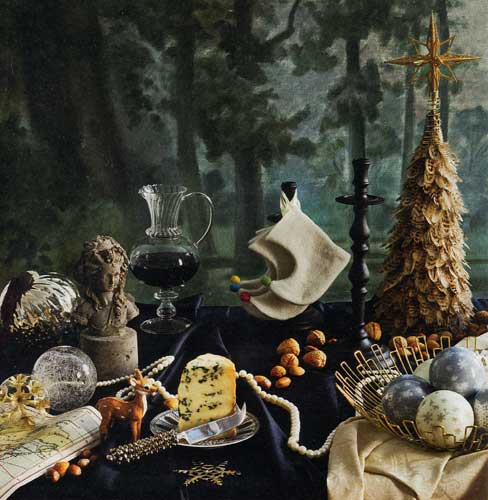

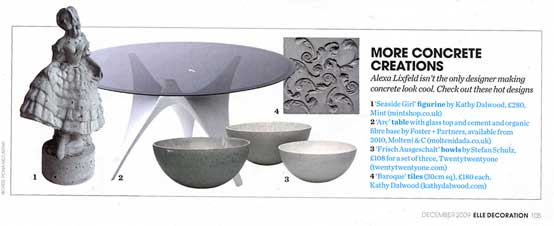

December

09

featuring figurines

and concrete baroque tiles

January

2010 featuring

tassel

tile figurines

concrete

urn sculpture

Grand Masters feature 2008

link to Grand Designs Magazine

Casting a spell Grand Masters feature - Grand Designs Magazine

Words: Iona Singleton

Photography: Thomas Stewart

1

At

the age of seven, Kathy Dalwood hung up her

ballet slippers and set out on a path that would

eventually lead her to become a successful

designer whose pieces can be found in homes all

over the world, thanks to a recent collaboration

with Habitat. Today, working primarily in plaster

and concrete, her latest creations include

sculptural planters, vases and tiles, whose

monochrome surfaces are indented with bold

motifs borrowed from disparate architectural

styles such as Modernism and the Baroque.

‘My mother used

to drop me and my sister off at

the town hall for ballet lessons,’ remembers Kathy.

‘But I hated them, so I began sneaking off to the

library to pore over all the books on interiors –

I could sit and look at the pictures for hours.’

At this early age,

Kathy also whiled away many

an hour in the studio of her father, Hubert

Dalwood, a prominent sculptor in the Sixties

and Seventies, who cast his bold abstract works

in bronze and aluminium. It was at her father’s

feet that her penchant for plaster was born, as

she and her sister played with bits of clay and

attempted plaster casting for the first time.

Given this nascent love of all things three dimensional,

why did she go on to study painting at university?

‘It was a big mistake,’ she says ruefully.

Frustrated by the limitations of this

medium, Kathy soon dropped out of college and

went into teaching instead. But she couldn’t

suppress her creative tendencies for long. In a

display of reinvention that is characteristic of her

designs, she woke up one morning and decided it

was time to get back into creative work. She soon

made up for lost time, designing a range of

furniture based on the multifaceted, wonky café

tables and stools seen in Cubist paintings.

2

‘They

were functional, but they had a sculptural

edge to them, which I would say is true of all my

work. I think of myself as a sculptor, really.’

It was the late Eighties: Thatcher was prime

minister and the City was experiencing its

legendary ‘big bang’ that, in turn, fuel-injected

the design trade. ‘The word “designer” went from

being a noun to an adjective: everyone was

talking about “designer” clothes and furniture,’

says Kathy. ‘It was really at the beginning of that

whole boom in design as we know it now.’

Launching her new career in this era gave her

the freedom to experiment with one-off pieces,

selling through interior designers, shops and

galleries that specialised in unique designs.

As well as creating colourful furniture, she

experimented with rococo shapes in wrought

iron and made dramatic chandeliers with

bespoke pieces of glass made for her by a

company specialising in scientific implements.

Then,

10 years ago, a chance encounter with

a computer hard drive led her to return to her

plaster-casting roots. ‘Looking at its geometric

shape and the surface details, such as the lines of

the ventilation grill, I could see its potential as

a piece of abstract sculpture,’ says Kathy. The unfortunate bit

of kit was swiftly disassembled and used, along with other pieces of electronic

equipment, to create a mould for a collection of vases made from plaster

and concrete, which

subsequently sold like hot cakes.

‘I

just completely fell in love with the process of casting,’she says.

‘You take away the mould and you have this riveting moment when

you’ve just created an object out of nothing. In that second when

it comes out, your gut tells you whether it’s worked or not.’

3

Kathy

is a big fan of the work of Britart sculptor Rachel

Whiteread, but whereas Whiteread’s casts of the emptyspaces of baths

or the underside of chairs become immediate pieces of art, Kathy uses

casting as part of a design process. ‘I kept the idea of abstraction

but felt I had to make more conscious aesthetic decisions,’ she

explains.

Decisions such as pairing two seemingly incompatible

architectural styles – the pure geometry of Modernism and the elaborate

ornamentation of the Baroque – to create her satisfyingly sculptural

range of concrete planters. ‘I love the flat planes you find in

Modernism and civil engineering, so when I became interested in the Baroque,

I wanted to look at it in a new context by combining elements from the

two

periods.’

The result is a series of individually cast planters,

whose boxy shapes and smooth surfaces are indented with voluptuous baroque

curls and garlands inspired by eighteenth-century facades.

Kathy cites London’s

iconic Southbank Centre as a source of inspiration for her recent Habitat

collection, which came about when their head of design and accessories

spotted herstylish modernist Setsquares tiles and commissioned her to

create a new line of tiles and vases for their stores.

‘I see buildings as sculptures, so it’s very easy for me to

reduce their scale and turn them into domestic objects,’ she says.

Her simple casting method mirrors that used to create the concrete building

blocks of the Southbank Centre.

Suddenly,

her work was in stores all over the world. ‘It was fantastic to

see the finished pieces because they were so brilliantly made and they

stuck very closely to my original prototypes.’

The prototypes were made in Kathy’s studio – a large, sunlit

room on the first floor of the home that she shares with her partner,

artist Justin Mortimer. The air is thick with the smell of the latex that

is setting in moulds on the floor, and a thin

layer of plaster dust has settled over every surface. Books and maquettes

jostle for space on the shelves that line the pale walls, and above her

desk, rows of casts inspired by industrial grain silos stand side-by-side

with an assortment of miniature Louis XV chairs. Among the works of art

on display is a painting by Justin of a black bin bag – an example

of how this couple give new meaning to overlooked objects.

4

Inside, cool white walls and grey-painted floors provide the perfect neutral

backdrop to showcase the couple’s colourful finds, collected on

regular visits to French street markets and a recent trip to Georgia,

USA, which they spent rummaging in thrift stores.

‘Our home is like our very own Sir John Soane’s

Museum (a house built by Soane as a resting

place for his own works of art), in that it houses

our many collections,’ laughs Kathy.

Her passion for reinvention, so obvious in her design

work, is also evident in the way in which these

once-humble objects are lovingly displayed

throughout the house – in the living room,

clusters of cut-glass candlesticks picked up in

local charity shops glint in the light that pours

in from the generously proportioned windows;

old tapestries have been transformed into stylish

cushions or used to upholster chairs, and

reproduction Louis XV-style furniture has been

given a new lease of life with a lick of paint.

In the kitchen, sleek

units, designed by Kathy,

are topped with worktops reclaimed from school

science laboratories – here and there you can

still see the graffiti etched into their surfaces.

Cantilevered cupboard doors house the couple’s

more everyday objects. In addition to her

sculptural work, Kathy runs a successful interior

design business, Shift, injecting her successful

blend of simple white spaces filled with colourful

French period furniture and accessories into

other people’s home. ‘The first thing I usually

do for my clients is rationalise the space by

designing cupboards and hidden storage

systems. I believe that everything you own

should have a designated home.’

Upstairs lies the

bathroom, with its sculptural

modern basin and eighteenth-century-style

wallpaper, and a master bedroom, with views

of the garden’s enormous lilac tree and carefully

curated selection of her planters. The guest

bedroom is home to a set of china figurines, some

of which Kathy has cast in stark grey concrete

as part of her new, more figurative designs.

‘I love the monochrome of my work, but after

our long holidays in France, it’s great coming

back to our colourful home,’ enthuses Kathy.

‘I suppose, in an ideal world, I’d like to live in an

eighteenth-century French chateau,’ she laughs,

‘but it would probably have to have a modernist

studio built on the back.’?

click to view PDF version

HABITAT film Every Product Tells a Story

commissioned by Habitat to follow the story of the kathy dalwood setsquares collection which were

designed exculsively for Habitat stores link to film...

selected press (with links to appropriate collection + to magazine / newspaper)

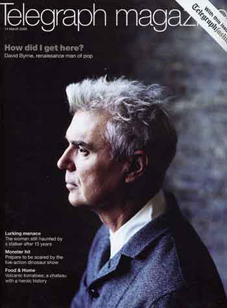

| CASTING

DIRECTOR |

featuring

concrete figurine collection

link to Telegraph

Magazine

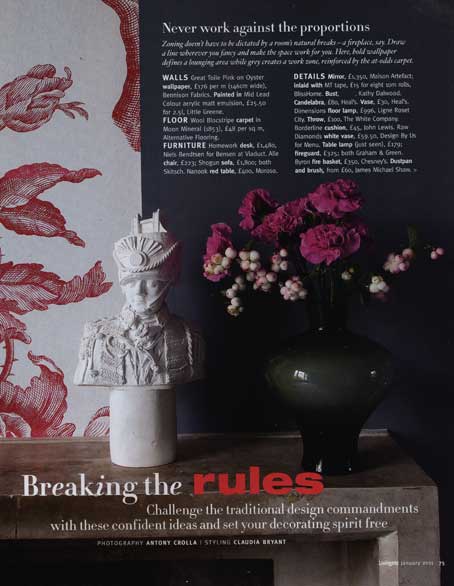

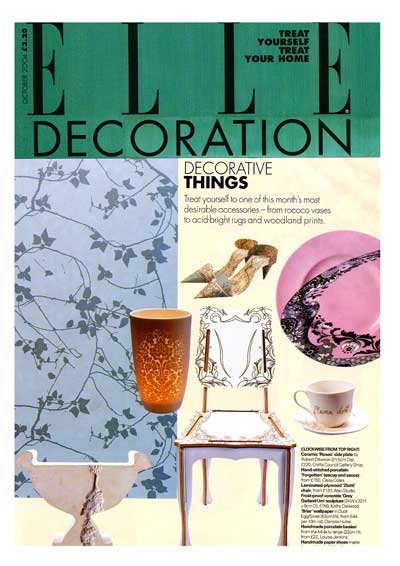

link to Living Etc featuring concrete figurine collection

link to Homes & Gardens feature featuring concrete figurine collection

link to

Period

Living magazine featuring

concrete figurine collection

featuring concrete figurine collection

link to Wallpaper magazine featuring concrete planters

link

to concrete baroque tiles

featuring concrete urn sculptures and concrete baroque tiles

featuring concrete planters and concrete urn sculpture

featuring concrete planters

featuring concrete planters link to Telegraph Magazine

concrete soap dish collection